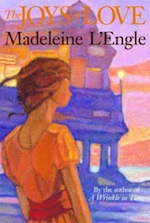

In 2008, after the death of Madeleine L’Engle, her granddaughters agreed to publish The Joys of Love, an early novel that had been rejected by several publishers. For whatever reason, L’Engle never made use of her status as a published author to print it later in her life. It’s a pity. The Joys of Love, written in the late 1940s, may not rank among L’Engle’s best, or offer the profound statements of her later books, but it is a happy, light and enjoyable read.

The Joys of Love centers on four days in the life of Elizabeth Jerrold. Elizabeth has always wanted to be an actress, and considers herself lucky to have gotten an apprenticeship with a summer stock company. It might seem rather less lucky to others: Elizabeth has to pay $20 a week for room and board (a considerably larger sum in 1946) for the dubious pleasure of working her fingers to the bone doing secretarial work and selling tickets in between occasional bouts of acting classes and rehearsals. It’s not all misery, however: when not working or rehearsing, the apprentices and the actors wander up and down the beach and the boardwalk, consuming hamburgers and milkshakes (refreshingly, few of the women are watching their weight) and having profound discussions about acting.

Plus, Elizabeth has fallen in love. It’s her first time, so the flaws are less apparent to her than to her friends, who can see that Kurt is not exactly ready for a serious relationship, especially one with Elizabeth. And they and readers can also see what Elizabeth cannot: her friend Ben is wildly in love with her, and would be a much better match in every way. But just as everything seems wonderful, Aunt Harriet, who has been funding this $20 a week, shocked that Elizabeth has allowed the other men of the group to see her in—gasp—pajamas—announces that she will no longer be funding Elizabeth’s apprenticeship.

(We don’t get enough details about the pajamas to determine if this is as shocking as Aunt Harriet thinks it is, but given that Elizabeth also bounces around in a bathing suit which has been mended more than once, and—hold your shock until the end of this sentence—also goes to a man’s dressing room, like TOTALLY ALONE, and even kisses him there, I’m guessing the pajamas may not be her worst offense, and some of you might not even disapprove. But those with very innocent minds should be warned.)

You can pretty much guess (correctly) where the novel is going after the first chapter or so, although L’Engle provides a few minor plot twists here and there. As it turns out, Aunt Harriet has some justification for her anti-theatre feelings. Elizabeth engages in a small rivalry with an annoying actress called Dottie (portions of this feel particularly drawn from L’Engle’s own experiences in small acting companies). She learns a bit more about the pasts of her new friends, and gets a sharp reminder that World War II was painful for some people.

Portions of the book have become very dated, although I did get a twinge of nostalgia with nearly every financial reference, before remembering that wages were low then too. And L’Engle occasionally makes Elizabeth a bit too gullible, a bit too innocent, to be believed. But on the other hand, the book also has a scene where a character calls Elizabeth out on her own statements, a scene that feels genuine and real, but not as judgmental as later scenes would be in L’Engle’s work. And it is filled with incidental details about theatre life and lessons of acting and the gossipy nature of the acting world, tied together with a very sweet, very believable romance. If you need a light comfort read, this may be well worth checking out.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida with two cats.